The Remarkable Legacy of the Dreamcast Port of Grand Theft Auto 3

The Dreamcast shone brightly from 1998 until 2001, but Sega’s financial struggles notoriously cut its lifespan short. Consequently, numerous games—both launched and unannounced—were cancelled, and as unconventional titles appeared on alternative platforms, many fans wondered if these games could have been experienced on the Dreamcast as well. Fortunately, with an unofficial homebrew release of Grand Theft Auto 3 on the classic Sega console, we now have answers to at least some of those questions.

GTA 3 certainly requires no introduction—it was a cultural phenomenon, after all! However, before GTA 3 captivated the world, the development team at DMA Design, known for Lemmings, had previously released various Grand Theft Auto titles across PlayStation, PC, and indeed, the Dreamcast. This is noteworthy—GTA2 received a port to Dreamcast during its brief lifespan. The outcome is undoubtedly sharp, but as a game originally created for PlayStation, it comes with limitations. It runs rather poorly on the Dreamcast, which feels disappointing given its origins. Nevertheless, setting that aside, many of the mechanics that would define the series began here. GTA was popular but not as mainstream as it would become after the release of GTA 3. The Dreamcast version, regrettably, suffers from relatively low fidelity, given the system it operates on, which only amplifies the impressive nature of GTA 3’s port.

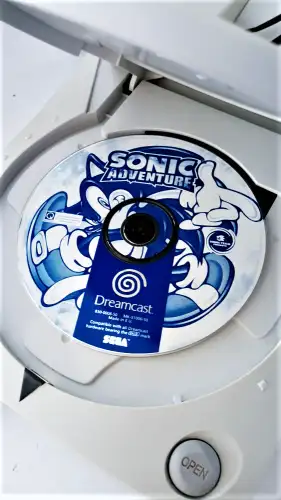

The new Dreamcast version is sourced from the RE3 reverse engineering project—a complete ground-up, non-emulated version of the Rockstar Engine. When crafting a playable version, developers extract data from the PC version and convert it to suitable file formats. It is currently optimized for use with Optical Disc Emulators, which replace the Dreamcast’s optical drive, although it is also possible to run it from a burned CD-R, albeit with some drawbacks. Essentially, this is a full version of GTA 3. All missions, maps, cutscenes, and audio are intact, although there are some compromises in quality that we will discuss.

Beginning with the comparisons, GTA 3 has seen numerous releases throughout the years, but I aimed to stay current and evaluate it against the latest PlayStation 2 release. In capturing the game, I used original consoles, outfitted with the PixelFX Gem for pristine HDMI digital output.

So, the first aspect I need to address is typically a visual feature that I did not incorporate in many comparisons—the so-called ‘trails’ effect. This is a motion blur effect that uses previous frames to create a type of post-process motion blur appearance. It also blends colors to produce that distinctive look that is central to GTA 3’s visual style. The Dreamcast struggles with this type of effect due to its peculiar memory architecture, which affects how it handles textures and framebuffers. Essentially, when attempting to use the framebuffer as a texture—a copy of the complete frame—you get two pixels correctly followed by two incorrect pixels. There are two selectable options in the Dreamcast version, but the performance impact is noticeable, and it’s evident that additional work is necessary.

Right away, I noticed some minor texture blending issues here, but also discrepancies in the character model. The Dreamcast version extracts data from the PC version, which includes alterations to character models, resulting in fundamental differences—and even some additional items that are absent on PS2. I also observed that texture resolution had been compromised to fit within the Dreamcast’s memory constraints. During the conversion process from the PC data, textures were reduced across the board compared to other versions of GTA 3. Now, this may seem odd, but according to SKMP (the project lead), it all boils down to memory limitations, though not necessarily related to the textures themselves.

In general, the game sends a significant amount of vertex data to the GPU, which must store all these vertices in memory before rendering them. While models appear simple at first glance, the large size and the number of objects on screen mean that GTA 3 pushes a substantial amount of geometry around. While the Dreamcast features 8MB of VRAM versus 4MB on the PS2, due to how it operates, vertex data consumes more than half of the system’s VRAM pool. Factor in framebuffer data and other VRAM resident objects, and that leaves approximately 2.3MB of VRAM available for textures.

Furthermore, in addition to reducing size, all textures are compressed using the Dreamcast’s VQ texture compression. However, it turns out that VQ compression is not well-suited for compressing the palette-based textures used in GTA 3, leading to increased visual artifacts as well. There is still hope, however. The team is working on solutions to address these issues, and in time, we may still see stable builds capable of loading full resolution textures. I also observed issues with light flares from headlights clipping through the environment. This is an ongoing concern for the team—there’s currently a depth mismatch occurring, and these light flares are generally 2D objects projected on top of the world geometry. Nevertheless, these are the main visual concerns I’ve noted because, otherwise, what we have now is quite close to the original game.

On a more positive note, all the major visual elements have made the transition—the lightmaps, shadow textures from trees and light posts, light halos, illumination from street lamps and traffic signals, fog effects, and more. It’s all here. One of the more remarkable aspects of this port is the streaming engine—part of this stems from GTA 3 being designed around optical disc-based data streaming, allowing for a great deal of flexibility. However, it remains challenging, especially considering that the Dreamcast has half the system memory of the PS2. The game attempts to keep as much data in memory as possible to avoid hiccups while a separate streaming thread manages data fetching from the source media.